Crypto and Raw Materials – Lessons from 25 years on the raw materials market.

Before my partner Daniel Masters and I discovered cryptocurrencies in 2013, we were active in commodity trading for almost three decades.

One of the features of bitcoin that appealed to us back then was the limited supply, which is limited to 21 million Bitcoin. This characteristic shares similarities with the finite nature of gold or silver.

Well-known patterns

The longer I work with bitcoin now, the more I see similar patterns emerging.

Firstly, one of the rules for success that we used in our Global Advisors Commodity Investment Fund in 2002-2007 were the “three Ds” — demand, depletion and the dollar. In a sense, the same forces are now present in the digital asset ecosystem:

- Demand in the form of increased value for digital assets, beyond financial speculation.

- As we will emphasize later, institutional interest, although in our experience it is increasing, is unrelated to demand.

- Mining in the form of periodically halving the reward for mining bitcoin.

- The dollar in the form of a fiat currencies with decreasing confidence following the 2008 global financial crisis, the use of measures such as “quantitative easing” and the current mini currency war between the US and China.

At least we see a similar pattern here…

Secondly, between the mid-1990s and the peak of the cycle in 2008, commodities evolved from a market of professionals and industry participants, to a widely recognized asset class. At the end of 2008, there were more than $250 billion in commodity index funds (up from $20 billion in 2002), and the gross market value of commodity derivatives increased 25-fold between June 2003 and June 2008, to $2.13 trillion.

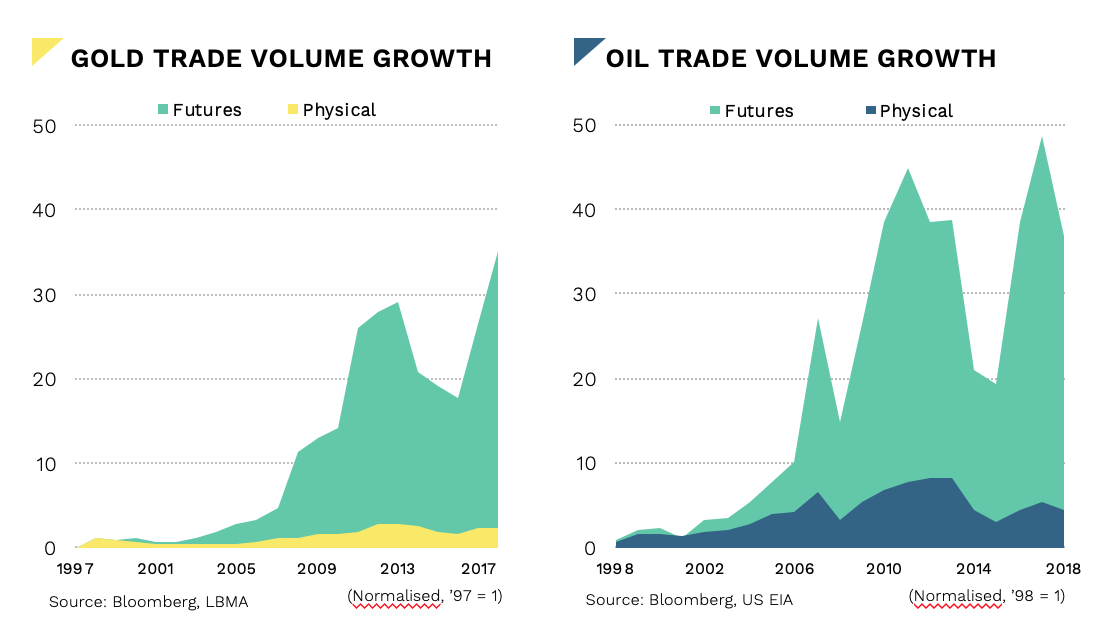

This expansion appears to have been supported by the emergence of a broader range of easy-to-market, non-physical, exchange-traded products. Since no one actually wanted to buy barrels of oil and take delivery accordingly, they preferred to speculate on the price of the underlying asset through synthetic instruments. The growth of the gold and oil market, as illustrated below, was primarily driven by futures and products that were independent of the underlying physical asset in every respect except price.

When I talk about institutional money flowing into the commodity sector, it is important to note that simplification has been an important factor in market growth. This growth has been synthetic or non-physical. First slowly, then quickly.

There is a similar tension today behind the idea of “institutional capital” entering the market for digital assets. It is highly unlikely that a large institutional buyer would want to buy bitcoin and process it digitally. It is much more likely that these institutional investors will take a synthetic exposure that offers them the price volatility of digital assets without all the underlying execution and operational risk.

For years there has been a quiet inflow into the underlying asset (in this case bitcoin) and a slow recovery as alternative easier investment opportunities (such as futures and exchange-traded products) have come to the market. I’ll let you infer from history what would follow cyclically.

“Blockchain not Bitcoin”

Third, I have definitely heard the “blockchain, not bitcoin” column before; or in other words, I have seen investors in an asset class bring together the different types of exposure early on.

In the early 2000s, many institutional investors were simply not convinced that they themselves needed access to commodities, although exposure to commodities is possible through investments in mining and oil stocks. My answer to that is yes and no.

Take the example of a company like BP – they are exposed to oil and gas prices, sure. But they are also exposed to refineries’ margins, to operational risks – as the Deepwater Horizon disaster showed – and to environmental policies with new regulations that affect demand. So no, in this case, buying BP is not the same as buying oil prices for an investor who wants to be exposed to the price of oil. Effectively, one is also buying other risks and other potential upside risks.

Similarly, so-called “junior mining” stocks can feel like options on the price of the commodity, but – even after a gold deposit has been discovered – it can still take many years to get the necessary permits to build a mine. To the leyman, a “junior mining company” is an exploration company looking for new deposits of gold, silver, uranium or other precious metals. Many so-called “junior mining” stocks are penny stocks and highly speculative, risky investments, which investors hopefully buy into before the company reaches the mother lode.

As a result, stock indices such as the OSX (PHLX Oil Services Sector) or the GDM (NYSE Arca Gold Miners) track the price of oil and gold, but not perfectly. The ebb and flow in the relationship between the value of the stock and the underlying asset is determined by many factors.

“We see a similar bipolar investment (and liquidity) spectrum emerging in the digital asset space.”

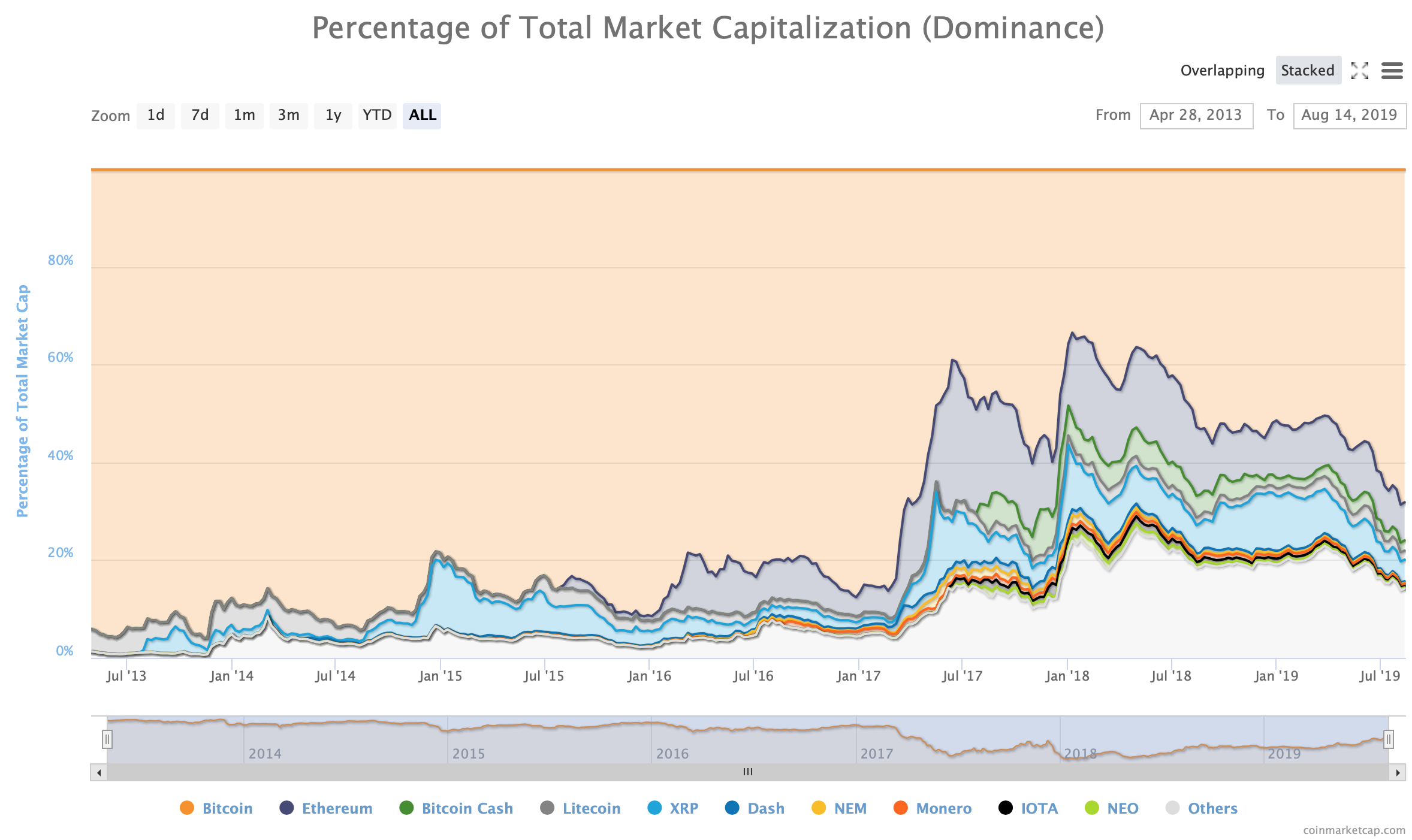

With the lion’s share of liquidity and awareness, bitcoin has led the market and is, if you will, the flagship investment. Although during much of the bitcoin rally in 2017, the professional money was also often looking elsewhere, as the ICO phenomenon at that time fueled the purchase of ethereum.

Altcoins and “Junior Miner” shares

At the other end of the liquidity spectrum we have the long tail of the “altcoins”, which in our opinion contains more than a few scams and very optimistic “business plans”. It also covers some very interesting and innovative technologies.

These tokens behave more like the “junior miners” or exploration stocks of the stock market: a short riot on some news that can inflate the price, but until there are real signs of solid development, not much happens. My partner Meltem Demirors has further expanded the symbolic investment in onshore shale gas development as an analogy. Did I mention that we are commodity people?

The Gartner Group describes this phase of its hype cycle as a “valley of disillusionment”. The year 2018 was without question a bottom of disillusionment for digital assets. Many old coins subsequently corrected by more than 90% from their all-time highs reached in late 2017 / early 2018. Bitcoin also corrected by more than 80% from a high of over $19,000 in December 2017 to below $3,500 in December 2018.

But I think the reality is that at some point in the (probably not too distant) future nobody cares anymore if a technology is “powered by blockchain”. Just like nobody cares today that the internet is powered by TCP/IP and HTTPS. When the hype fades, all consumers and businesses care about is that the stuff works. And that is the most important lesson of all.

Crypto projects, whether at the protocol level via a token, or at the application level via a product or service, must use technology that works and that people want to use. It must be better than what is already available. We see some of these technologies emerging in 2019 and we expect them to accelerate through 2020 and beyond.

At CoinShares, we believe in this shift from the old capital markets to digitalized, block-based financial markets. The story continues what it has done before, and as my partner Ryan Radloff has pointed out earlier, this is a natural development, not a revolution.

We have turned away from the question of “if” this development is coming and started to analyze “when, where and how” this will happen and how we can best participate in this value creation.

We are therefore excited about the opportunities that lie ahead and are aware that the “three D’s” – demand, depletion and the dollar – that have served as a compass for us in the past, still point us in the right direction.